Definition and Concept of Debt Overhang

Debt overhang refers to a situation where a company’s existing debt obligations hinder its ability to raise new debt or invest in new projects. This concept was first highlighted by Stewart Myers in his 1977 hypothesis, which posits that highly leveraged firms are less likely to secure additional financing due to the burden of their existing debts. Unlike regular corporate debt, which can be managed through various financial strategies, debt overhang creates a significant barrier to future investments.

- Mastering Death Taxes: Strategies to Minimize Your Estate’s Tax Liability

- How Fractional Shares Revolutionize Investing: Affordable Access to Any Stock

- How Corporate Bonds Work: A Comprehensive Guide to Investing in Corporate Debt

- How Currency Carry Trades Work: Profit from Interest Rate Differentials in Forex Markets

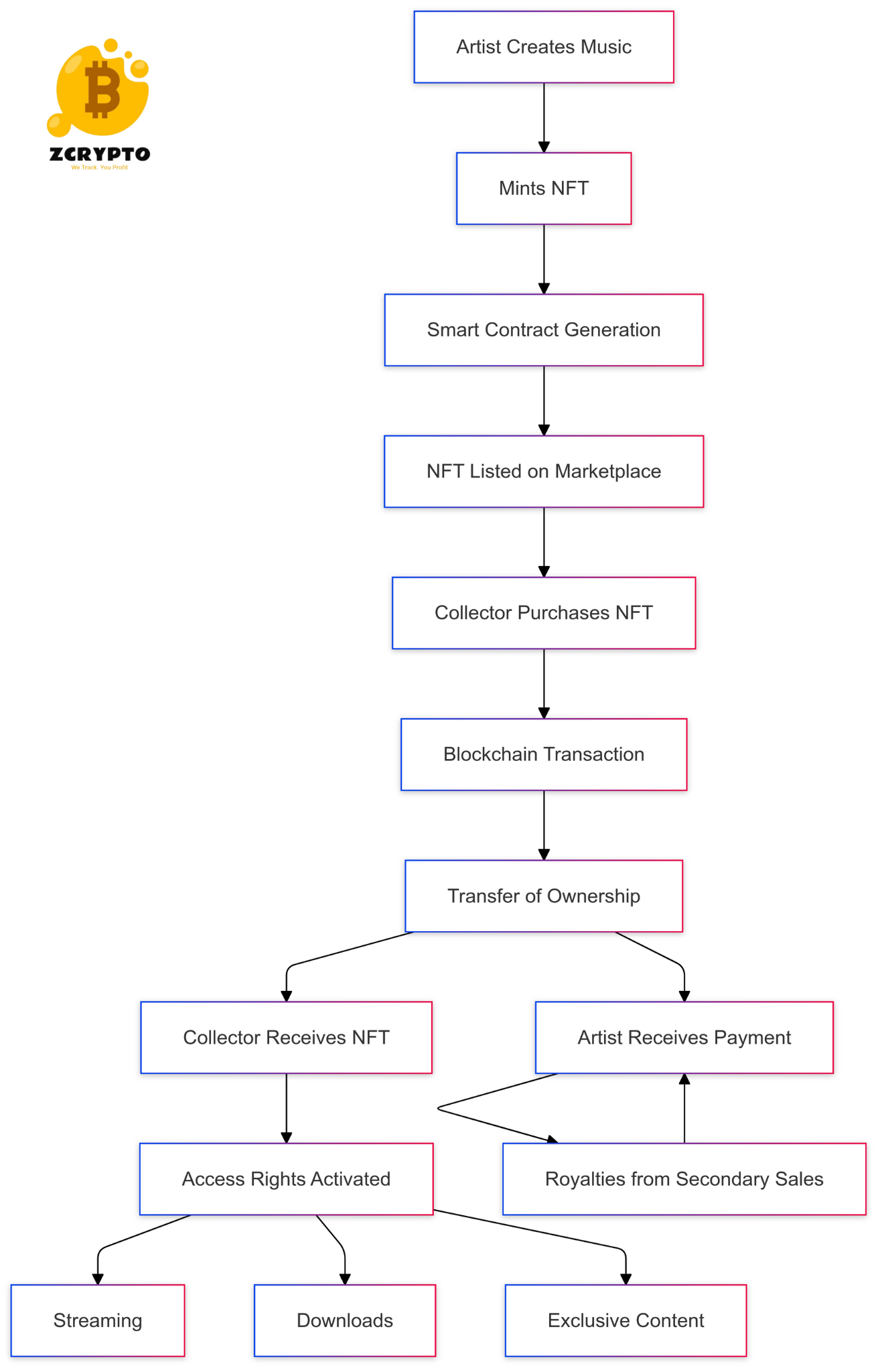

- What is Music NFT? Transforming Artist-Fan Relationships

Impact of Debt Overhang on Corporate Investment

Firm-Level Evidence

Empirical studies have consistently shown that corporate debt overhang significantly discourages investment at the firm level. For instance, highly leveraged firms tend to invest less than those with lower debt-to-asset ratios. This nonlinear effect means that as the level of indebtedness increases, the negative impact on investment becomes even more pronounced. Companies burdened with high levels of debt often find themselves in a vicious cycle where they cannot generate enough cash flow to service their debts, let alone invest in growth opportunities.

Bạn đang xem: How Debt Overhang Impacts Corporate Investment and Economic Growth

Sector and Size-Specific Effects

The impact of debt overhang varies across different firm sizes and sectors. Large firms, which often have more complex financial structures, are particularly vulnerable to the effects of debt overhang. Similarly, firms in sectors that require significant capital expenditures, such as manufacturing or construction, are more likely to feel the pinch of high indebtedness. Smaller firms, while generally more agile, may also suffer if they are heavily leveraged and lack the financial buffers to weather economic storms.

Role of Macroeconomic and Financial Conditions

Macroeconomic and financial conditions can amplify the negative effects of debt overhang on investment. During times of economic uncertainty, such as the COVID-19 pandemic, firms with high levels of debt face increased challenges. The pandemic highlighted how quickly financial markets can become volatile, making it even harder for indebted firms to access new credit or roll over existing debts. This environment exacerbates the reduction in investment, as firms become more risk-averse and focus on survival rather than growth.

Mechanisms Through Which Debt Overhang Affects Investment

Rollover Risk and Short-Term Debt

One of the key mechanisms through which debt overhang affects investment is through rollover risk, particularly for firms holding short-term debt. In countries with weak banking systems or those experiencing sovereign stress, firms may find it difficult to roll over their short-term debts. This creates a liquidity crisis that further reduces their ability to invest in new projects or even maintain current operations.

Financial Constraints and Liquid Assets

Xem thêm : Understanding the Chinese Wall: A Crucial Barrier in Finance and Investment Banking

Financially constrained firms with low liquid assets are another group heavily impacted by debt overhang. These firms often cut back on investment, including intangible assets like employee training and brand development. The lack of liquid assets means they cannot respond quickly to new opportunities or mitigate risks effectively, leading to a decline in overall investment.

Borrowing Costs and Risk Repricing

High levels of debt also lead to increased borrowing costs and a repricing of risk. As firms accumulate more debt, lenders perceive them as riskier borrowers, leading to higher interest rates on new loans. This increased cost of capital further constrains firms’ ability to invest, creating a cycle where high debt levels become self-reinforcing barriers to growth.

Economic Growth and Aggregate Demand

Aggregate Demand and Investment Growth

The impact of debt overhang extends beyond individual firms to affect the broader economy. Weaker investment growth due to debt overhang contributes to slower economic growth by reducing aggregate demand. When many firms are unable to invest, the overall demand for goods and services decreases, leading to a slowdown in economic activity.

Corporate Zombies and Inefficient Debt Restructuring

The concept of corporate zombies—firms that are financially distressed but continue to operate inefficiently—also plays a role here. Inefficient debt restructuring and liquidation processes allow these firms to linger, impeding economic growth. These zombie firms consume resources that could be better allocated to healthier, more productive businesses, thereby hindering overall economic efficiency.

Policy Implications and Recommendations

Mitigating Debt Overhang Effects

To mitigate the effects of debt overhang, policymakers can implement several strategies. Employment protection programs and credit guarantee schemes can support firms without exacerbating their indebtedness. These measures help maintain employment levels and ensure that firms have access to necessary credit without increasing their debt burdens.

Improving Financial Stability

Xem thêm : Unlocking E-Mini Futures: A Comprehensive Guide to Trading and Investment Opportunities

Improving financial stability is crucial for preventing excessive debt build-ups. This can be achieved through better debt restructuring mechanisms and closer monitoring of corporate leverage. By ensuring that firms do not accumulate unsustainable levels of debt, policymakers can prevent the negative impacts of debt overhang from materializing in the first place.

References

-

Myers, S. C. (1977). Determinants of Corporate Borrowing. Journal of Financial Economics, 5(2), 147-175.

-

Lang, L., & Stulz, R. M. (1992). Contagion and Competitive Intra-Industry Effects of Bankruptcy Announcements. Journal of Financial Economics, 30(1), 45-60.

-

Hennessy, C. A., & Whited, T. M. (2007). How Costly Is External Financing? Evidence from a Structural Estimation. Journal of Finance, 62(4), 1705-1745.

-

Caballero, R. J., Hoshi, T., & Kashyap, A. K. (2008). Zombie Lending and Depressed Restructuring in Japan. American Economic Review, 98(5), 1943-1977.

-

Acharya, V. V., & Steffen, S. (2015). The “Greatest” Carry Trade Ever? Understanding Eurozone Bank Risks. Journal of Financial Economics, 115(2), 215-236.

Nguồn: https://factorsofproduction.shop

Danh mục: Blog

Leave a Reply